(C) 2013 Rafe M. Brown. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

We provide the first report on the herpetological biodiversity (amphibians and reptiles) of the northern Sierra Madre Mountain Range (Cagayan and Isabela provinces), northeast Luzon Island, Philippines. New data from extensive previously unpublished surveys in the Municipalities of Gonzaga, Gattaran, Lasam, Santa Ana, and Baggao (Cagayan Province), as well as fieldwork in the Municipalities of Cabagan, San Mariano, and Palanan (Isabela Province), combined with all available historical museum records, suggest this region is quite diverse. Our new data indicate that at least 101 species are present (29 amphibians, 30 lizards, 35 snakes, two freshwater turtles, three marine turtles, and two crocodilians) and now represented with well-documented records and/or voucher specimens, confirmed in institutional biodiversity repositories. A high percentage of Philippine endemic species constitute the local fauna (approximately 70%). The results of this and other recent studies signify that the herpetological diversity of the northern Philippines is far more diverse than previously imagined. Thirty-eight percent of our recorded species are associated with unresolved taxonomic issues (suspected new species or species complexes in need of taxonomic partitioning). This suggests that despite past and present efforts to comprehensively characterize the fauna, the herpetological biodiversity of the northern Philippines is still substantially underestimated and warranting of further study.

Biodiversity, Cagayan River Valley, Cordillera Mountain Range, Sierra Madre Mountain Range, Northern Philippines

The highly distinctive terrestrial vertebrate fauna of the northeastern Philippines has been the subject of intense interest, speculation, and debate since the first historical explorations of the northern extremes of the archipelago (Wallace 1860, 1876; Everett 1889; Boulenger 1894; Stejneger 1907; Hoogstral 1951; Allen et al. 2004, 2006). Although many past and recent explorations of this unique part of southeast Asia highlighted spectacular endemic species (Stejneger 1907; Ota and Ross 1994; Brown et al. 2008, 2009; Oliveros et al. 2011), the dominant view of the Philippines by the beginning of the 20th century was the biogeographer’s concept of a “fringing” archipelago (Dickerson 1928; Kloss 1929; Darlington 1957; Myers 1960 1962; Brown and Alcala 1970a; Siler et al. 2012). According to this perception, archipelagos near a continental source for invasion by vertebrate colonists should show distribution patterns consistent with the classic “immigrant pattern” of faunal distributions (Myers 1962; Brown and Alcala 1970a; Lomolino et al. 2010). Thus, early biogeographers expected species to be distributed along possible migration corridors, with various groups extending no further in distance from the continental source, than their relative dispersal abilities would allow (Taylor 1928; Inger 1954; Darlington 1957; Myers 1962; Carlquist 1965; Brown and Alcala 1970a). With respect to the northern Philippines, the most often-cited dispersal corridors included the western island arc (Borneo–Palawan–Mindoro) and the eastern Island chain (Sulu Archipelago–Mindanao–Leyte–Samar; Myers 1962; Esselstyn et al. 2004; Brown and Guttman 2002; Jones and Kennedy 2008; Brown et al. 2009), with more limited evidence in support of southward colonization from Taiwan (Taylor 1928; Kennedy et al. 2000; Esselstyn and Oliveros 2010).

In the context of this biogeographical world view, islands like Luzon, at the tail ends of island chains and possible dispersal routes from the continental source (Diamond and Gilpin 1983; Brown and Guttman 2002; Jones and Kennedy 2008; but see Taylor 1928; Kennedy et al. 2000; Esselstyn and Oliveros 2010) were viewed as the extreme end points of faunal dispersal and dispersion (Huxley 1868; Darlington 1928; Myers 1962; Esselstyn et al. 2004). As a consequence, numerous classic works consider the biodiversity of such islands as “depauperate” in the sense that they contained a reduced set of species shared with a continental mainland source (Dickerson 1928; Taylor 1928; Inger 1954; Brown and Alcala 1970a; Dickinson et al. 1991; de Jong 1996; Lomolino et al. 2010). The view of a depauperate Luzon fauna has persisted throughout the last half century in discussions of its herpetofauna (Inger 1954; Leviton 1963a; Brown and Alcala 1970a, 1978, 1980). Recently however, a renewed interest in faunistic studies of the northern Philippines (Brown et al. 1996, 2000a, 2007, 2012; Diesmos et al. 2005; Siler et al. 2011a) has produced a series of notable discoveries (Alcala et al. 1998, 1999; R. Brown et al. 1999, 2000b, 2008, 2009; W. Brown et al. 1997a, b, c, 1999a, b; Diesmos et al. 2002; Siler et al. 2009, 2010a, b; Linkem et al. 2010; Welton et al. 2010; Fuiten et al. 2011), drawing attention to high levels of species diversity, preponderance of inferred autochthonous speciation, and substantial endemism in the northern reaches of the archipelago (Diesmos et al. 2005; Brown and Diesmos 2009; Brown et al. 2012). Together these studies have suggested that the northern portions of the archipelago may, in fact, be substantially more biologically diverse than currently appreciated. Thus, it is conceivable that, despite past expectations, species richness at a given northern Luzon site may be potentially as high as that demonstrated for the southern portion of the archipelago, adjacent to the Sunda Shelf (Nuñeza et al. 2010; Siler at al. 2011; Diesmos et al. 2005; Diesmos and Brown 2011; Brown et al. 2012).

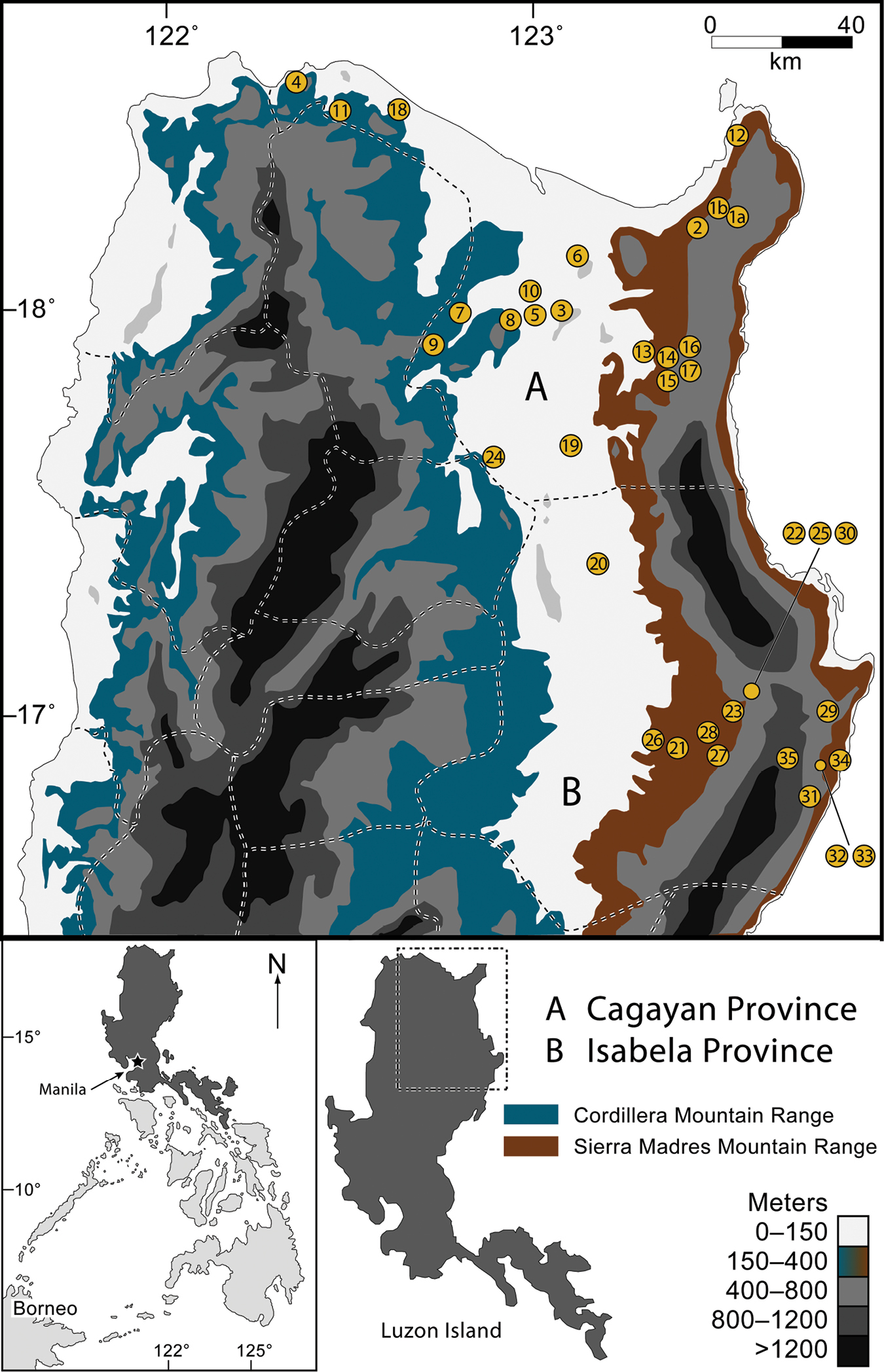

Recent works suggest that the northern end of Luzon Island (Fig. 1) and the islands between Luzon and Taiwan (Oliveros et al. 2011) represent the very last extent of conceivable dispersion of faunal elements of Sundaic origin (Dickerson 1928; Inger 1954, 1999; Inger and Voris 2001). Recent studies have considered the diversity of herpetofaunas of the islands north of Luzon (Oliveros et al. 2011) and the northern end of the Cordillera Mountains of northwest Luzon (Diesmos et al. 2005; Brown et al. 2012).

Map of northern Luzon Island, Philippines, with the Sierra Madre and Cordillera mountain ranges indicated (contour shading depicts elevational increments; see key, lower right). Provincial boundaries are indicated with dashed lines. Sampling localities marked with numbered circles, corresponding to localities listed in Table 1. The inset (bottom left) shows the location of Luzon Island (darkly shaded) within the Philippines.

Map of northern Luzon Island, Philippines, with the Sierra Madre and Cordillera mountain ranges indicated (contour shading depicts elevational increments; see key, lower right). Provincial boundaries are indicated with dashed lines. Sampling localities marked with numbered circles, corresponding to localities listed in Table 1. The inset (bottom left) shows the location of Luzon Island (darkly shaded) within the Philippines.

In this paper we take the first step towards gaining a better understanding of the faunal communities of the northeastern-most extreme of Luzon by considering the amphibians and reptiles of the northern Sierra Madre Mountains (Fig. 1). We provide the first attempt to synthesize the known herpetological diversity of Cagayan and Isabela provinces (Fig. 1), northern Luzon Island (see also van Beijnen 2007, Diesmos 2008). We present data from our own survey work, as well as those from historical museum collections derived from the northern Sierra Madre Mountains. Because very little has been published previously on the herpetological communities of the area, all of these records constitute major range extensions and substantial expansion of our knowledge of resident biodiversity. This work contributes to a growing body of recent literature demonstrating that the herpetological communities of Luzon Island are species rich, composed of high percentages of endemic taxa, and are regionally unique in comparisons to the other zoogeographical regions of Luzon (Auffenberg 1988; Brown et al. 1996, 2000a, 2012; Diesmos et al. 2005; Welton et al. 2010; Siler et al. 2011a; McLeod et al. 2011; Devan-Song and Brown 2012).

Cagayan and Isabela Provinces: Geography and Landscape. Cagayan and Isabela provinces lie at the extreme northeastern portion of Luzon (Fig. 1), with land areas totaling more than 9, 000 and 10, 664 square kilometers, respectively. Cagayan contains 28 municipalities and 825 barangays (villages) while Isabela contains 35 municipalities and 1018 barangays. Their capital cities are Tuguegarao and Ilagan, respectively. Inhabited by six major enthnolinguistic groups (Ilocanos, Ibanags, Malauegs, Itawis, Gaddangs, and Aetas), together they are home to more than 2.6 million human residents (NSO 2010).

Both Provinces are dominated by three strikingly distinct geographical and topographical features: the wide alluvial plains surrounding the Cagayan River valley, the northern extremes of a strikingly elongate north-south mountain range (The Sierra Madre; Figs 3–8), and the narrow strip of coastal forest along the north (Figs 2–3) and the east coasts of northern Luzon and the Philippine Sea (Fig. 1). Portions of the southwestern corner of Cagayan (bordering the province of Kalinga) and all of the western portions of Isabela (bordering Kalinga, Mountain, and Ifugao provinces) abut the foothills of the central Cordillera Mountains of Luzon (Fig. 1). Roughly a third of the land area of these provinces is near sea level; the majority of the remaining area constitutes the mountainous terrain of the northern Sierra Madre Mountain Range and the sprawling foothills to the west and east of this elongate mountain massif.

The Babuyan Island Group across the Balintang channel to the north of Luzon (Fig. 1) is included administratively in Cagayan Province; this biogeographically distinct region has recently been reviewed for its herpetofauna (Oliveros et al. 2011) and will not be treated in detail here.

View of the north coast of Luzon, along the boundary between west Cagayan Province and Ilocos Province (fig. 1). Photo: JS.

View of the north coast of Luzon, along the boundary between west Cagayan Province and Ilocos Province (fig. 1). Photo: JS.

View of the forested west coast of Isabela Province (Dinapique). Photo: MVW.

View of the Sierra Madre from the west, at the Municipality of Cabagan, Barangay Garita (Isabela Province). Photo: MVW.

View of the Sierra Madre from the west, at the Municipality of Cabagan, Barangay Garita (Isabela Province). Photo: MVW.

View of the northeast coast of Luzon from the foothills of Mt. Cagua, Municipality of Gonzaga. Note northern end of the Sierra Madre at right and Palaui Island in the background to the right. Photo: RMB.

View of the northeast coast of Luzon from the foothills of Mt. Cagua, Municipality of Gonzaga. Note northern end of the Sierra Madre at right and Palaui Island in the background to the right. Photo: RMB.

Ultrabasic forests above 1200 m at Barangay Diddadungan, Palanan, northern Isabela Province. Photo: MVW

Ultrabasic forests above 1200 m at Barangay Diddadungan, Palanan, northern Isabela Province. Photo: MVW

View south of the northern Sierra Madre (from peak of Mt. Cagua, Municipality of Gonzaga, Cagayan Province). Photo: LJW.

View south of the northern Sierra Madre (from peak of Mt. Cagua, Municipality of Gonzaga, Cagayan Province). Photo: LJW.

Mt. Cagua, Cagayan Province, with rice fields on the outskirts of Barangay Magrafil in the foreground. Photo: RMB.

We surveyed amphibian and reptile diversity at numerous sites throughout Cagayan and Isabela provinces (Table 2) using standardized sampling techniques (Heyer et al. 1994) and specimen collection and preservation methodology (Simmons 2002; ASIH 2004). Our most recent surveys (July–August, 2011) involved intensive elevational transects at the extreme northern end of the Sierra Madre Mountain Range in the Mt. Cagua area (Municipality of Gonzaga, Barangays Magrafil and and Santa Clara; Fig. 1). Surveys were conducted in early mornings, mid-day, afternoons, and evenings by experienced teams of four to eight individuals, sampling a wide variety of habitat types within each general study location. Habitats included dry forest on ridges, moist ravines, forest trails at all elevations, dry intermittent streambeds, small streams, large rivers, forest gaps and edges, and grassy open areas (Figs 9–17). Investigators at each sampling location made extensive surveys of each area (on foot) to ascertain habitat types and then visited each at varying times of the day. Nocturnal searches (1800–2400 hr) were conducted at each habitat type, within each sampling site, on dry and rainy nights. By concentrating field survey efforts to span the end of the dry season and the beginning of the rainy season (June–August) we were able to assure that each habitat type at each location was sampled under differing atmospheric conditions.

Sampling Locations. Data presented here include results of our own surveys (Table 1) and a variety of collections, both intensive and incidental, from major U.S. Museum collections (see acknowledgements). In addition, an extensive series of collections housed at the USNM (field work of R. I. Crombie), KU and PNM (field work of ACD and surveys of MVW, EJ, and DR) targeted several localities to the south, in central Cagayan Province and Isabela Province. To be as comprehensive as possible in our treatment of Cagayan and Isabela, we include all of these records here, with the caveat that methods of surveying herpetological communities most likely differed among collection efforts and locations.

Cagayan and Isabela localities where amphibian and reptile specimens have been collected or observed (see Materials and Methods).

| Location | Municipality | Barangay/Barrio | GPS coordinates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cagayan | ||||

| 1a | Gonzaga | Barangay Magrafil | Mt. Cagua crater | 18.213N, 122.110E |

| 1b | Gonzaga | Barangay Magrafil | Mt. Cagua low elevation | 18.236N, 122.104E |

| 2 | Gonzaga | Barangay Santa Clara | Purok 7 | 18.228N, 122.060E |

| 3 | Gattaran | Barangay Nassiping | 18.054N, 121.641E | |

| 4 | Santa Praxedes | Taggat Forest Reserve | 18.580N, 121.010E | |

| 5 | Lasam | Lasam Centro | 18.051N, 121.600E | |

| 6 | Lasam | Battalan Barrio | 18.171N, 121.723E | |

| 7 | Lasam | Cabatacan Barrio | 18.072N, 121.480E | |

| 8. | Lasam | Alannay Barrio | 18.053N, 121.551E | |

| 9 | Lasam | Vintar Barrio | 18.045N, 121.43E | |

| 10 | Lasam | San Pedro | 18.081N, 121.597E | |

| 11 | Santa Ana | Barangay San Vicente, | Sitio Angib | 18.490N, 121.168E |

| 12 | Santa Ana | Santa Ana Centro | 18.482N, 122.1569E | |

| 13 | Baggao | Barrio Santa Margarita | 17.923N, 121.960E | |

| 14 | Baggao | Road between Barrio San Miguel and Barrio Imurung | 17.914N, 121.988E | |

| 15 | Baggao | Barrio Via | Vicinity of hot springs on bank of Ital river | 17.887N, 121.986E |

| 16 | Baggao | Barrio San Miguel | 17.917N, 122.000E | |

| 17 | Baggao | Barrio Imurung | 17.898N, 122.001E | |

| 18 | Pamplona | ca. 4 km NW of Abulug River Bridge | 18.464N, 121.339E | |

| 19 | Solana | Barrio Nabbutuan | 17.658N, 121.683E | |

| 20 | Peñablanca | Barangay Malibabag | Callao Caves area | 17.677N, 121.8444E |

| Isabela | ||||

| 21 | Cabagan | Barangay Garita, Mitra Ranch | 17.417N, 121.8231E | |

| 22 | San Mariano | Barangay Binatug | 16.954N, 122.0669E | |

| 23 | San Mariano | Barangay Dibuluan, Apaya Creek area | Sitio Apaya | 17.029N, 122.1928E |

| 24 | San Mariano | Barangay Dibuluan, Dunoy Lake area | Sitio Dunoy | 16.995N, 122.1579E |

| 25 | San Mariano | Barangay Del Pilar | 16.8592N, 122.104E | |

| 26 | San Mariano | Barangay Dibuluan, Dibanti Ridge, Dibanti River area | 17.015N, 122.2036E | |

| 27 | San Mariano | Barangay Alibadabad | 16.964N, 122.0451E | |

| 28 | San Mariano | San Jose | 16.934N, 122.1275E | |

| 29 | San Mariano | Barangay Disulap | 16.963N, 122.1250E | |

| 30 | Palanan | Barangay Didian | Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park | 16.970N, 122.4122E |

| 31 | San Mariano | Barangay Dibuluan | Catalangan River | 17.024N, 122.1794E |

| 32 | Palanan | Barangay Diddadungan | Dyadyadin, ultrabasic forest | 16.798N, 122.3922E |

| 33 | Palanan | Barangay Diddadungan | Pangden, lowland dipterocarp forest | 16.833N, 122.4181E |

| 34 | Palanan | Barangay Diddadungan | Limestone forest near Magsinaraw cave | 16.941N, 122.4536E |

| 35 | Palanan | Barangay Diddadungan | Coastal habitat, Divinisa | 16.834N, 122.4319E |

| 36 | Palanan | Barangay Didian | Dipagsanghan, lowland dipterocarp forest | 16.879N, 122.3447E |

| 37 | Maconacon | Barangay Reina Mercedes | Blos River | 17.508N, 122.1916E |

| Location | Municipality | Barangay/Barrio | GPS coordinates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cagayan | ||||

| 1a | Gonzaga | Barangay Magrafil | Mt. Cagua crater | 18.213N, 122.110E |

| 1b | Gonzaga | Barangay Magrafil | Mt. Cagua low elevation | 18.236N, 122.104E |

| 2 | Gonzaga | Barangay Santa Clara | Purok 7 | 18.228N, 122.060E |

| 3 | Gattaran | Barangay Nassiping | 18.054N, 121.641E | |

| 4 | Santa Praxedes | Taggat Forest Reserve | 18.580N, 121.010E | |

| 5 | Lasam | Lasam Centro | 18.051N, 121.600E | |

| 6 | Lasam | Battalan Barrio | 18.171N, 121.723E | |

| 7 | Lasam | Cabatacan Barrio | 18.072N, 121.480E | |

| 8. | Lasam | Alannay Barrio | 18.053N, 121.551E | |

| 9 | Lasam | Vintar Barrio | 18.045N, 121.43E | |

| 10 | Lasam | San Pedro | 18.081N, 121.597E | |

| 11 | Santa Ana | Barangay San Vicente, | Sitio Angib | 18.490N, 121.168E |

| 12 | Santa Ana | Santa Ana Centro | 18.482N, 122.1569E | |

| 13 | Baggao | Barrio Santa Margarita | 17.923N, 121.960E | |

| 14 | Baggao | Road between Barrio San Miguel and Barrio Imurung | 17.914N, 121.988E | |

| 15 | Baggao | Barrio Via | Vicinity of hot springs on bank of Ital river | 17.887N, 121.986E |

| 16 | Baggao | Barrio San Miguel | 17.917N, 122.000E | |

| 17 | Baggao | Barrio Imurung | 17.898N, 122.001E | |

| 18 | Pamplona | ca. 4 km NW of Abulug River Bridge | 18.464N, 121.339E | |

| 19 | Solana | Barrio Nabbutuan | 17.658N, 121.683E | |

| 20 | Peñablanca | Barangay Malibabag | Callao Caves area | 17.677N, 121.8444E |

| Isabela | ||||

| 21 | Cabagan | Barangay Garita, Mitra Ranch | 17.417N, 121.8231E | |

| 22 | San Mariano | Barangay Binatug | 16.954N, 122.0669E | |

| 23 | San Mariano | Barangay Dibuluan, Apaya Creek area | Sitio Apaya | 17.029N, 122.1928E |

| 24 | San Mariano | Barangay Dibuluan, Dunoy Lake area | Sitio Dunoy | 16.995N, 122.1579E |

| 25 | San Mariano | Barangay Del Pilar | 16.8592N, 122.104E | |

| 26 | San Mariano | Barangay Dibuluan, Dibanti Ridge, Dibanti River area | 17.015N, 122.2036E | |

| 27 | San Mariano | Barangay Alibadabad | 16.964N, 122.0451E | |

| 28 | San Mariano | San Jose | 16.934N, 122.1275E | |

| 29 | San Mariano | Barangay Disulap | 16.963N, 122.1250E | |

| 30 | Palanan | Barangay Didian | Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park | 16.970N, 122.4122E |

| 31 | San Mariano | Barangay Dibuluan | Catalangan River | 17.024N, 122.1794E |

| 32 | Palanan | Barangay Diddadungan | Dyadyadin, ultrabasic forest | 16.798N, 122.3922E |

| 33 | Palanan | Barangay Diddadungan | Pangden, lowland dipterocarp forest | 16.833N, 122.4181E |

| 34 | Palanan | Barangay Diddadungan | Limestone forest near Magsinaraw cave | 16.941N, 122.4536E |

| 35 | Palanan | Barangay Diddadungan | Coastal habitat, Divinisa | 16.834N, 122.4319E |

| 36 | Palanan | Barangay Didian | Dipagsanghan, lowland dipterocarp forest | 16.879N, 122.3447E |

| 37 | Maconacon | Barangay Reina Mercedes | Blos River | 17.508N, 122.1916E |

Amphibians (anurans) and reptiles (lizards , snakes, turtles, and crocodiles) from Cagayan Province, andIsabela Province (to the south; together the two provinces make up the northern Sierra Madre Mountain Range, of Luzon Island; Fig. 1). N = new provincial record (observed during this study, with voucher specimen). P = previously reported literature records for Cagayan or Isabela provinces (with vouchered specimens of photographic evidence deposited in museum collections). O = new observation (no voucher specimens collected). R = Range extension within Cagayan and/or Isabela Province. * = Luzon faunal region (Brown and Diesmos 2002, 2009) endemics; n= 46.

| AMPHIBIA | Cagayan | Isabela |

| Bufonidae | ||

| Rhinella marina (Linnaeus, 1758) | N | P |

| Ceratobatrachidae | ||

| Platymantis cagayanensis Brown, Alcala & Diesmos, 1999* | P, R | N |

| Platymantis corrugatus (Duméril, 1853) | N | N |

| Platymantis cornutus (Taylor, 1922)* | N | N |

| Platymantis polillensis (Taylor, 1922)* | N | |

| Platymantis pygmaeus Alcala, Brown & Diesmos, 1998* | N | P |

| Platymantis sierramadrensis Brown, Alcala, Ong & Diesmos, 1999* | N | P |

| Platymantis taylori Brown, Alcala & Diesmos, 1999* | P | |

| Platymantis sp. “Yokyok” * | N | N |

| Platymantis sp.2 “Cheep-cheep” * | N | N |

| Platymantis sp.3 “See-yok” * | N | N |

| Platymantis sp. | N | N |

| Dicroglossidae | ||

| Fejervarya moodiei (Taylor, 1920) | N | |

| Fejervarya vittigera (Wiegmann, 1834) | N | N |

| Hoplobatrachus rugulosus (Wiegmann, 1834) | N | N |

| Limnonectes macrocephalus (Inger, 1954)* | N | P |

| Limnonectes woodworthi (Taylor, 1923)* | N | N |

| Occidozyga laevis (Günther, 1859) | P | N |

| Microhylidae | ||

| Kaloula kalingensis Taylor, 1922* | N | P |

| Kaloula rigida Taylor, 1922* | N | N |

| Kaloula picta (Duméril & Bibron, 1841) | N | N |

| Kaloula pulchra Gray, 1825 | N | N |

| Ranidae | ||

| Hylarana similis (Günther, 1873)* | N | P |

| Sanguirana luzonensis (Boulenger, 1896)* | N | P |

| Sanguirana tipanan (Brown, McGuire & Diesmos, 2000)* | P | |

| Rhacophoridae | ||

| Philautus surdus (Peters, 1863) | N | N |

| Polypedates leucomystax Gravenhorst, 1829 | N | N |

| Rhacophorus pardalis Günther, 1859 | N | N |

| Rhacophorus appendiculatus (Günther, 1858) | N | |

| REPTILIA (Lizards) | ||

| Agamidae | ||

| Bronchocela marmorata Gray, 1845 | N | N |

| Draco spilopterus (Wiegmann, 1834) | N, P | N |

| Gekkonidae | ||

| Cyrtodactylus philippinicus (Steindacher, 1867) | N | N |

| Gehyra mutilata (Wiegmann, 1834) | O | N |

| Gekko gecko (Linnaeus, 1758) | N | N |

| Gekko kikuchii (Oshima, 1912) | N | N |

| Hemidactylus frenatus Duméril & Bibron, 1836 | O | N |

| Hemidactylus platyurus (Schneider, 1792) | O | |

| Hemidactylus stejnegeri Ota & Hikida, 1989 | N | |

| Lepidodactylus cf. lugubris (Duméril & Bibron, 1836) | N | N |

| Luperosaurus cf. kubli Brown, Diemsos & Duya, 2007* | N | N |

| Pseudogekko compressicorpus (Taylor, 1915) | N | |

| Scincidae | ||

| Brachymeles bicolor (Gray, 1845)* | N | P |

| Brachymeles bonitae Duméril & Bibron, 1839 | N | N |

| Brachymeles kadwa Siler & Brown, 2010* | P | |

| Brachymeles muntingkamay Siler, Rico, Duya & Brown, 2009* | N | |

| Eutropis cumingi (Brown & Alcala, 1980) | N | N |

| Eutropis multicarinata borealis Brown & Alcala, 1980 | N | N |

| Eutropis multifasciata (Kuhl, 1820) | O | N |

| Lamprolepis smaragdina philippinica Mertens, 1829 | N | N |

| Lipinia cf. vulcania Girard, 1857 | N | |

| Otosaurus cumingi Gray, 1845 | N | N |

| Pinoyscincus abdictus aquilonius (Brown & Alcala, 1980) | N | N |

| Parvoscincus decipiens (Boulenger, 1895)* | N | N |

| Parvoscincus cf. decipiens* | N | N |

| Parvoscincus leucospilos (Peters, 1872)* | O | N |

| Parvoscincus steerei (Stejneger, 1908) | N | N |

| Parvoscincus tagapayao (Brown, McGuire, Ferner & Alcala, 1999)* | N | N |

| Varanidae | ||

| Varanus marmoratus (Wiegmann, 1834)* | N | P |

| Varanus bitatawa Welton, Siler, Bennet, Diesmos, Duya, Dugay, Rico, Van Weerd & Brown, 2010* | P, R | P |

| REPTILIA (Snakes) | ||

| Colubridae | ||

| Ahaetulla prasina preocularis (Taylor, 1922) | N | N |

| Boiga cynodon (Boie, 1827) | N | N |

| Boiga dendrophila divergens Taylor, 1922* | N | |

| Boiga philippina (Peters, 1867)* | N | |

| Calamaria bitorques Peters, 1872* | N | N |

| Calamaria gervaisi Duméril & Bibron, 1854 | N | N |

| Coelognathus erythrurus manillensis (Jan, 1863)* | N | P |

| Cyclocorus lineatus lineatus (Reinhardt, 1843)* | N | N |

| Dendrelaphis luzonensis Leviton, 1961* | N | N |

| Dendrelaphis marenae Vogel & van Rooijen, 2008 | N | N |

| Dryophiops philippina Boulenger, 1896 | N | N |

| Gonyosoma oxycephalum (Boie, 1827) | N | N |

| Hologerrhum philippinum Günther, 1858* | N | N |

| Lycodon capucinus (Boie, 1827) | N | N |

| Lycodon muelleri Duméril, Bibron & Duméril, 1854* | N | |

| Lycodon solivagus Ota & Ross, 1984* | N | |

| Oligodon ancorus (Girard, 1858) * | N | |

| Psammodynastes pulverulentus (Boie, 1827) | N | N |

| Pseudorhabdion cf. mcnamarae (Taylor, 1917)* | N | |

| Pseudorhabdion cf. talonuran Brown, Leviton & Sison, 1999* | N | |

| Ptyas luzonensis (Günther, 1873) | N | |

| Rhabdophis spilogaster (Boie, 1827) | N | N |

| Tropidonophis dendrophiops (Günther, 1883) | N | N |

| Elapidae | ||

| Hemibungarus calligaster (Wiegmann, 1835)* | N | |

| Naja philippinensis Taylor, 1922; Ophiophagus hannah (Cantor, 1836) | NN | |

| Homolopsidae | ||

| Cerberus schneideri (Schlegel, 1837) | N | |

| Lamprophiidae | ||

| Oxyrhabdium leporinum leporinum (Günther, 1858)* | N | |

| Pythonidae | ||

| Python reticulatus (Schneider, 1801) | N | P |

| Typhlopidae | ||

| Ramphotyphlops braminus (Daudin, 1803) | N | N |

| Typhlops ruficaudus (Gray, 1845)* | N | |

| Typhlops sp. 1* | N | |

| Typhlops sp. 2* | N | |

| Viperidae | ||

| Trimereserus flavomaculatus (Gray, 1842) | N | N |

| Tropidolaemus subannulatus (Gray, 1842) | O | |

| REPTILIA (Turtles) | ||

| Geomydidae | ||

| Cuora amboinensis amboinensis (Daudin, 1802) | P | N |

| Trionychidae | P | P, O |

| Pelochelys cantorii Gray, 11864 | P | P, O |

| Cheloniidae | ||

| Caretta caretta (Linnaaeus, 1758) | O | |

| Chelonia mydas (Linnaaeus, 1758) | O | |

| Eretmochelys imbricata (Linnaaeus, 1766) | O | |

| Crocodylidae | ||

| Crocodylus mindorensis Schmidt, 1935 | P, O | P, O |

| Crocodylus porosus Schneider, 1801 | P, O | P, O |

| AMPHIBIA | Cagayan | Isabela |

| Bufonidae | ||

| Rhinella marina (Linnaeus, 1758) | N | P |

| Ceratobatrachidae | ||

| Platymantis cagayanensis Brown, Alcala & Diesmos, 1999* | P, R | N |

| Platymantis corrugatus (Duméril, 1853) | N | N |

| Platymantis cornutus (Taylor, 1922)* | N | N |

| Platymantis polillensis (Taylor, 1922)* | N | |

| Platymantis pygmaeus Alcala, Brown & Diesmos, 1998* | N | P |

| Platymantis sierramadrensis Brown, Alcala, Ong & Diesmos, 1999* | N | P |

| Platymantis taylori Brown, Alcala & Diesmos, 1999* | P | |

| Platymantis sp. “Yokyok” * | N | N |

| Platymantis sp.2 “Cheep-cheep” * | N | N |

| Platymantis sp.3 “See-yok” * | N | N |

| Platymantis sp. | N | N |

| Dicroglossidae | ||

| Fejervarya moodiei (Taylor, 1920) | N | |

| Fejervarya vittigera (Wiegmann, 1834) | N | N |

| Hoplobatrachus rugulosus (Wiegmann, 1834) | N | N |

| Limnonectes macrocephalus (Inger, 1954)* | N | P |

| Limnonectes woodworthi (Taylor, 1923)* | N | N |

| Occidozyga laevis (Günther, 1859) | P | N |

| Microhylidae | ||

| Kaloula kalingensis Taylor, 1922* | N | P |

| Kaloula rigida Taylor, 1922* | N | N |

| Kaloula picta (Duméril & Bibron, 1841) | N | N |

| Kaloula pulchra Gray, 1825 | N | N |

| Ranidae | ||

| Hylarana similis (Günther, 1873)* | N | P |

| Sanguirana luzonensis (Boulenger, 1896)* | N | P |

| Sanguirana tipanan (Brown, McGuire & Diesmos, 2000)* | P | |

| Rhacophoridae | ||

| Philautus surdus (Peters, 1863) | N | N |

| Polypedates leucomystax Gravenhorst, 1829 | N | N |

| Rhacophorus pardalis Günther, 1859 | N | N |

| Rhacophorus appendiculatus (Günther, 1858) | N | |

| REPTILIA (Lizards) | ||

| Agamidae | ||

| Bronchocela marmorata Gray, 1845 | N | N |

| Draco spilopterus (Wiegmann, 1834) | N, P | N |

| Gekkonidae | ||

| Cyrtodactylus philippinicus (Steindacher, 1867) | N | N |

| Gehyra mutilata (Wiegmann, 1834) | O | N |

| Gekko gecko (Linnaeus, 1758) | N | N |

| Gekko kikuchii (Oshima, 1912) | N | N |

| Hemidactylus frenatus Duméril & Bibron, 1836 | O | N |

| Hemidactylus platyurus (Schneider, 1792) | O | |

| Hemidactylus stejnegeri Ota & Hikida, 1989 | N | |

| Lepidodactylus cf. lugubris (Duméril & Bibron, 1836) | N | N |

| Luperosaurus cf. kubli Brown, Diemsos & Duya, 2007* | N | N |

| Pseudogekko compressicorpus (Taylor, 1915) | N | |

| Scincidae | ||

| Brachymeles bicolor (Gray, 1845)* | N | P |

| Brachymeles bonitae Duméril & Bibron, 1839 | N | N |

| Brachymeles kadwa Siler & Brown, 2010* | P | |

| Brachymeles muntingkamay Siler, Rico, Duya & Brown, 2009* | N | |

| Eutropis cumingi (Brown & Alcala, 1980) | N | N |

| Eutropis multicarinata borealis Brown & Alcala, 1980 | N | N |

| Eutropis multifasciata (Kuhl, 1820) | O | N |

| Lamprolepis smaragdina philippinica Mertens, 1829 | N | N |

| Lipinia cf. vulcania Girard, 1857 | N | |

| Otosaurus cumingi Gray, 1845 | N | N |

| Pinoyscincus abdictus aquilonius (Brown & Alcala, 1980) | N | N |

| Parvoscincus decipiens (Boulenger, 1895)* | N | N |

| Parvoscincus cf. decipiens* | N | N |

| Parvoscincus leucospilos (Peters, 1872)* | O | N |

| Parvoscincus steerei (Stejneger, 1908) | N | N |

| Parvoscincus tagapayao (Brown, McGuire, Ferner & Alcala, 1999)* | N | N |

| Varanidae | ||

| Varanus marmoratus (Wiegmann, 1834)* | N | P |

| Varanus bitatawa Welton, Siler, Bennet, Diesmos, Duya, Dugay, Rico, Van Weerd & Brown, 2010* | P, R | P |

| REPTILIA (Snakes) | ||

| Colubridae | ||

| Ahaetulla prasina preocularis (Taylor, 1922) | N | N |

| Boiga cynodon (Boie, 1827) | N | N |

| Boiga dendrophila divergens Taylor, 1922* | N | |

| Boiga philippina (Peters, 1867)* | N | |

| Calamaria bitorques Peters, 1872* | N | N |

| Calamaria gervaisi Duméril & Bibron, 1854 | N | N |

| Coelognathus erythrurus manillensis (Jan, 1863)* | N | P |

| Cyclocorus lineatus lineatus (Reinhardt, 1843)* | N | N |

| Dendrelaphis luzonensis Leviton, 1961* | N | N |

| Dendrelaphis marenae Vogel & van Rooijen, 2008 | N | N |

| Dryophiops philippina Boulenger, 1896 | N | N |

| Gonyosoma oxycephalum (Boie, 1827) | N | N |

| Hologerrhum philippinum Günther, 1858* | N | N |

| Lycodon capucinus (Boie, 1827) | N | N |

| Lycodon muelleri Duméril, Bibron & Duméril, 1854* | N | |

| Lycodon solivagus Ota & Ross, 1984* | N | |

| Oligodon ancorus (Girard, 1858) * | N | |

| Psammodynastes pulverulentus (Boie, 1827) | N | N |

| Pseudorhabdion cf. mcnamarae (Taylor, 1917)* | N | |

| Pseudorhabdion cf. talonuran Brown, Leviton & Sison, 1999* | N | |

| Ptyas luzonensis (Günther, 1873) | N | |

| Rhabdophis spilogaster (Boie, 1827) | N | N |

| Tropidonophis dendrophiops (Günther, 1883) | N | N |

| Elapidae | ||

| Hemibungarus calligaster (Wiegmann, 1835)* | N | |

| Naja philippinensis Taylor, 1922; Ophiophagus hannah (Cantor, 1836) | NN | |

| Homolopsidae | ||

| Cerberus schneideri (Schlegel, 1837) | N | |

| Lamprophiidae | ||

| Oxyrhabdium leporinum leporinum (Günther, 1858)* | N | |

| Pythonidae | ||

| Python reticulatus (Schneider, 1801) | N | P |

| Typhlopidae | ||

| Ramphotyphlops braminus (Daudin, 1803) | N | N |

| Typhlops ruficaudus (Gray, 1845)* | N | |

| Typhlops sp. 1* | N | |

| Typhlops sp. 2* | N | |

| Viperidae | ||

| Trimereserus flavomaculatus (Gray, 1842) | N | N |

| Tropidolaemus subannulatus (Gray, 1842) | O | |

| REPTILIA (Turtles) | ||

| Geomydidae | ||

| Cuora amboinensis amboinensis (Daudin, 1802) | P | N |

| Trionychidae | P | P, O |

| Pelochelys cantorii Gray, 11864 | P | P, O |

| Cheloniidae | ||

| Caretta caretta (Linnaaeus, 1758) | O | |

| Chelonia mydas (Linnaaeus, 1758) | O | |

| Eretmochelys imbricata (Linnaaeus, 1766) | O | |

| Crocodylidae | ||

| Crocodylus mindorensis Schmidt, 1935 | P, O | P, O |

| Crocodylus porosus Schneider, 1801 | P, O | P, O |

The forested edge of the Mt. Cagua volcanic crater with the northern Sierra Madre in the background. Photo: RMB.

The forested edge of the Mt. Cagua volcanic crater with the northern Sierra Madre in the background. Photo: RMB.

Natural grassland area on the edge of Mt. Cagua volcanic crater. Photo: JS.

Appearance of lower edge of cloud forest, 1250 m, Mt. Cagua. Photo: RMB.

Volcanic vent on the forested floor of the Mt. Cagua crater. Photo: LJW.

Appearance of Mt. Cagua cloud forest below the canopy at 1250 m asl. Photo: RMB.

Mature forest at Location 1a in the crater floor of Mt. Cagua. Photo: JS.

Unnamed waterfall at Location 1a in the crater floor of Mt. Cagua. Photo: JS.

Streamside habitat typical of Limnonectes macrocephalus, Hylarana similis, Sanguirana luzonensis, and Platymantis sp. 2 (near Location 1a). Photo: LJW.

Streamside habitat typical of Limnonectes macrocephalus, Hylarana similis, Sanguirana luzonensis, and Platymantis sp. 2 (near Location 1a). Photo: LJW.

Signs of illegal timber poaching on the boundary of the Mt. Cagua protected area, Location 2. Photo: RMB.

We document 101 species of amphibians and reptiles from Cagayan and Isabela provinces, including 29 frog species, 30 lizards, 35 snakes, two freshwater turtles, three marine turtles, and two crocodilian taxa (Table 2). Taken together this diversity represents approximately 35% percent of the total Philippine herpetofauna (approximately 350 species; Brown 2007; Brown et al. 2008; Diesmos et al. 2002; Diesmos and Brown 2011; Brown and Stuart 2012) and 70% of the taxa recorded are Philippine endemics. Below we provide accounts for each species, provide notes on their natural history and habitat, and highlight many unresolved taxonomic problems (involving 38% of the species included) that are relevant to particular taxa. We also comment on the conservation status of individual species when data presented here suggest that existing conservation status assessments (IUCN 2010, 2011) are out of date (Siler et al. 2011; McLeod et al. 2011; Brown et al. 2012) or will soon require revision.

Family Bufonidae

Rhinella marina (Linnaeus, 1758)

Rhinella marina (Fig. 18) is a non-native species that may have originally been introduced to the Philippines during the industrial revolution and the major sugar cane agricultural production boom on the central Philippine island of Negros (Brown and Alcala 1970a; Alcala and Brown 1998; Diesmos et al. 2006). Since its introduction it has spread widely throughout the country and has been found throughout low elevation agricultural areas where densities may be particularly high (Alcala 1957; Afuang 1994), in foot hills of major mountains, and even as high as 1200 masl in selected areas (RMB, CDS, ACD, personal observation). Our specimens (only a few collected among the many encountered) were located on trails in selectively logged forests, at mid elevations, and near forest edges and shifting agricultural plantations.

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330585; Location 5: USNM 498512–15, PNM 7424.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307440.

Family Ceratobatrachidae

Platymantis cagayanensis Brown, Alcala & Diesmos, 1999

Originally described from extreme northwest Cagayan Province at the Municipality of Santa Praxedes along the border with Ilocos Norte Province (Brown et al. 1999b), this species is now known to be widespread throughout the north coast of Luzon, including the northern ends of the Cordillera and Sierra Madre Mountain ranges (Alcala and Brown 1998, 1999; Brown et al. 2012). The identification of this species in the field is complicated by its variable coloration, tuberculate dorsal surfaces, and moderate body size, a suite of characters it shares with many frogs in the Platymantis dorsalis species group (Alcala and Brown 1998, 1999). However, this species may be reliably diagnosed in life from its sympatric congeners Platymantis sp. “seeyok” and Platymantis sp. “yok-yok” (see below) by its bright yellow or yellow-orange iris color above the pupil (Fig. 19) and its distinct advertisement calls, sounding to the human ear like “Eeeerrr-root” or “Kreeee-eek” (Brown et al. 1999b; personal observation). Our observation of this species as locally abundant, widespread, and commonly encountered in northern Cagayan Province supports Brown et al.’s (2012) downgrading of its conservation status from “Vulnerable” to “Near Threatened” (IUCN 2010, 2011).

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330300–01; Location 1b: KU 330302–26; Location 3: PNM 7614–24; Location 4: CAS 207447–50 (paratypes); PNM 6691 (holotype), 6692–93 (paratypes).

Isabela Province—Location 36: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Platymantis cagayanensis (KU 330716) from mid-elevation of Mt. Cagua (Location 1b). Note diagnostic yellow coloration of upper iris. Photo: RMB.

Platymantis cagayanensis (KU 330716) from mid-elevation of Mt. Cagua (Location 1b). Note diagnostic yellow coloration of upper iris. Photo: RMB.

Platymantis corrugatus (Duméril, 1853)

Platymantis corrugatus (Fig. 20), as presently recognized, is a widespread endemic species found throughout the archipelago. There is considerable color pattern variation, but the species can be generally diagnosed by its medium body size, some form of a dark (gray, brown, or black) facial mask, and elongate tubercular ridges running along the dorsal surface. We observed this species at many locations calling most intensively at sunset (1800–1900 hr) after which it only called intermittently. The species commonly calls from beneath some kind of ground cover (leaf of other debris) on the forest floor. Its call sounds to the human ear like a raspy “whaaah…whaaah.”

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330249–54: Location 1b: KU 330255–63; Location 11: PNM 6453; Location 15: USNM 498730.

Isabela Province—Location 30: PNM 6448, MVW photo voucher.

Platymantis corrugatus (KU 330255) from mid-elevation of Mt. Cagua (Location 1b) Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Platymantis corrugatus (KU 330255) from mid-elevation of Mt. Cagua (Location 1b) Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Platymantis cornutus (Taylor 1922)

Originally described on the basis of a single specimen from Balbalan, Kalinga, in the northern Cordillera Mountain Range (holotype CAS 231501; Taylor 1920, 1922a), this species (Fig. 21) is widespread, commonly encountered, and locally abundant (given sufficient precipitation) at mid- to high-elevation sites in the Sierra Madre Range (Brown et al. 2000a; 2012; Diesmos et al. 2005; Siler et al. 2011a). We have no reliable records of any other member of the Platymantis guentheri Group (Brown et al. 1997b, 1997c) of frogs at the same localities where Platymantis cornutus has been recorded in the mountains of extreme northern Luzon, rendering our confidence in this identification very high. Platymantis cornutus calls from understory vegetation immediately following rain and is most frequently encountered on axils and along fronds of aerial ferns. This species deposits direct-developing embryos in small clutches (6–8 eggs) on fern axils (Brown et al. 2012). It has one of the most rapid advertisement calls of any Philippine Platymantis, sounding to the human ear like “Tuk-tuk-tuk-tuk…” with 10–20 rapidly-delivered individual pulses. Geographic records reported here contribute to the continued expansion of this species’ range throughout much of northern Luzon, supporting Brown et al.’s (2012) action of downgrading this species from “Vulnerable” (VU) to “Near Threatened” (IUCN 2011).

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330362–89; Location 1b: KU 330390–92.

Platymantis cornutus (KU 330390) from mid-elevation of Mt. Cagua (Location 1b). Note diagnostic yellow inguinal coloration and white infratympanic tubercle. Photo: RMB.

Platymantis cornutus (KU 330390) from mid-elevation of Mt. Cagua (Location 1b). Note diagnostic yellow inguinal coloration and white infratympanic tubercle. Photo: RMB.

Platymantis polillensis (Taylor 1922)

Platymantis polillensis (Fig. 22) is a small, herbaceous-layer specializing arboreal species encountered most often in ferns and shrubs colonizing disturbed forest edges, secondary growth forest, forest gaps, and tree falls. Previously considered “Critically Endangered, ” or “Endangered” (IUCN 2011) and endemic to the island of Polillo (Quezon Province, off the coast of SE Luzon; holotype CAS 62250), this species is now known to be widespread, commonly encountered (given occurrence of precipitation and preferred habitat type), and often locally abundant (Brown et al. 2000a, 2012; Siler et al. 2011a; McLeod et al. 2011). The major range extension reported here supports Brown et al.’s (2012) downgrading of this species conservation status to “Near Threatened” (IUCN 2010) based on its additional presence in Aurora Province, southern Luzon. This species calls with a slow series of amplitude-modulated high frequency “chirps” following sufficient precipitation.

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330234–35; Location 1b: KU 330236–38.

Isabela Province—Location 33: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Female Platymantis polillensis (KU 330235) from mid elevation of Mt. Cagua (Location 1b). Photo: RMB.

Female Platymantis polillensis (KU 330235) from mid elevation of Mt. Cagua (Location 1b). Photo: RMB.

Platymantis pygmaeus Alcala, Brown & Diesmos, 1998

Platymantis pygmaeus (Fig. 23) was originally described from Palanan, Isabela Province, and is now known to be widespread and abundant in Bulacan, Quezon, Aurora, Kalinga, Isabela, Cagayan, and Ilocos Norte provinces (Alcala et al. 1998; Brown 2000b; Siler 2010; McLeod et al. 2011). The substantial distributional record reported here, while not surprising, constitutes additional evidence in support of Brown et al.’s (2012) downgrading of this species conservation status from “Vulnerable” (IUCN 2011) to “Near Threatened” (IUCN 2010). This is the smallest species of Platymantis in the Philippines (male SVL 12–15 mm) and it can be recognized in life by its high frequency “click-click-click…” advertisement call and its preference for calling from low (0.3–1.0 m), shrub layer vegetation.

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330239–43; Location 1b: KU 330244–48; Location 13: PNM 7800–01; Location 33: no specimen (MVW photo voucher).

Isabela Province—Location 30: CAS 204762–66 (paratypes), PNM 6255 (holotype), 7792–99; Location 33: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Platymantis pygmaeus (specimen not collected) at San Mariano (Location 33). Photo: MVW.

Platymantis pygmaeus (specimen not collected) at San Mariano (Location 33). Photo: MVW.

Platymantis sierramadrensis Brown, Alcaka, Ong & Diesmos, 1999

Platymantis sierramadrensis was described on the basis of specimens from Barangay Umiray, Municipality of General Nakar, Quezon Province (holotype PNM 6465), from Aurora Province (paratypes 204738, 204742–45), and other, non-type material from Palanan, Isabela Province (CAS 204739, 204740, CAS 204741). Subsequent confusion in identification of Platymantis sierramadrensis has involved a suspicion that two separate taxa may have been attributed to this species, a confusion that may have undermined the type description (Brown et al. 1999; Brown et al. 2000a, Siler et al. 2011a). Since the realization of this potential problem, we have twice noted (Brown et al. 2000a; Siler et al. 2011a) the presence of two sympatric small bodied Platymantis hazelae Group (Brown et al. 1997b) species, one of which appears to be most abundant at lower elevations (approximately 400–700 m) in disturbed habitats and another that is often encountered at the upper end of this elevational range, but is most abundant at elevations above 900 m. We consider the lower elevation species, with a “chirp” mating call, to be the widespread, common species Platymantis polillensis, and the slightly larger bodied, high elevation species, tentatively assigned to Platymantis sierramadrensis. The latter calls with a pure, constant frequency call, sounding to the human ear like the ringing of a small bell (thus differing from the “chirp” call of Platymantis polillensis). Current IUCN conservation classification for this species is “Vulnerable (B1ab(iii)), ” based on our assessment from 2004 (IUCN 2011). Considering the taxonomic confusion still surrounding this species, the lack of reliable past records, and the absence of any convincing evidence of population, area of occurrence, or habitat decline, we now consider this species to be “Data Deficient (DD; IUCN 2010, 2011). Once the taxonomy of this species is clarified with a return to the type locality in General Nakar to determine which call type occurs there, direct, field-based data gathered from natural populations (and not inferred from forest cover) will be necessary to reconsider a higher possible conservation threat level (IUCN 2011).

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330637–51.

Isabela Province—Location 30: CAS 204739–41; Location 36: PNM 6461–63, 6470–74.

Platymantis taylori Brown, Alcala, Diesmos, 1999

Since the time of its discovery (Brown et al. 1999), this species (Fig. 24) has been documented only at the Municipality of Palanan (Barangay Didian). This taxon was diagnosed primarily on the basis of its relatively large body size and distinctive advertisement call, sounding to the human ear like the buzz produced by a Geiger counter. This species previously has been classified by IUCN as “Endangered” (EN; B1ab(iii); IUCN 2011, 2011), on the basis of its purported limited range and anticipated decline in habitat due to the presence of logging at low elevations along Luzon’s east coast near Palanan.

Long overdue for a conservation status revision, we categorize this species as “Data Deficient” (DD) because (1) it has been recorded only once and no repeat surveys to the immediate or surrounding areas have been undertaken to determine the extent of its range, and (2) there is no evidence that this taxon requires intact, low-elevation forest and no evidence to suggest that it is range-restricted. Thus, there is no way to determine whether continued degradation of lowland coastal forests in Palanan will adversely affect this species. Originally characterized as “common and widespread” at the original collection site (Brown et al. 1999; IUCN 2004), its range presumably includes an extremely large protected area, supporting our conviction that this species must be downgraded to a low conservation threat category (e.g., “Near Threatened, ” NT) or, more appropriately, considered “Data Deficient” until some attempt is made to study it in the field and more surveys in surrounding areas are conducted. Platymantis taylori is another example of a case in which negative data have been used inappropriately for conservation status assessment (Brown et al. 2012), resulting in a higher level of threat category when, in reality, virtually nothing is known of its biology, natural history, habitat requirements, and actual conservation status.

Isabela Province—Location 21: PNM 8676; Location 26: ACD specimens deposited in PNM; Location 30: CAS 207440–46 (paratypes), PNM 6684, 8659–74, 8953.

Platymantis taylori (PNM 8676) from San Mariano (Location 29). Photo: ACD.

Platymantis taylori (PNM 8676) from San Mariano (Location 29). Photo: ACD.

Platymantis sp. 1 “Yokyok”

This distinctive form (Fig. 25) is now known from two sites in Cagayan and Isabela provinces (both between 400 and 500 m in disturbed forested habitats). We suspect that this possible undescribed species is much more widespread and will be frequently encountered if surveys can be conducted in intervening localities. This terrestrial species is slightly smaller than the morphologically similar Platymantis cagayanensis and Platymantis sp. 3 “seeyok, ” and calls with a long pulse train, sounding to the human ear like “Yok-yok-yok-yok….”

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330628–35.

Isabela Province—Location 3: KU 307608–09, 327587; Location 30: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Platymantis sp. 1 (“Yokyok;” KU 330628) from lower elevation Mt. Cagua, Municipality of Gonzaga, below Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Platymantis sp. 1 (“Yokyok;” KU 330628) from lower elevation Mt. Cagua, Municipality of Gonzaga, below Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Platymantis sp. 2 “Cheep-cheep”

We encountered another potentially distinct species (Fig. 26) of Platymantis at both high and low elevation sites on Mt. Cagua, Municipality of Gonzaga. The suspected new species appears phenotypically most similar to Platymantis lawtoni from Sibuyan Island (Brown and Alcala 1974; Alcala and Brown 1998, 1999), but is distinguished from other Luzon taxa by its distinct coloration, smooth dorsum, semi-aquatic microhabitat preference, and distinctive “cheep-cheep-cheep…” vocalizations.

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330588–330600; Location 1b: 330601–615.

Platymantis sp. 2 (“Cheep-cheep;” KU 330606) from the crater of Mt. Cagua, Location 1a. Photo: RMB.

Platymantis sp. 2 (“Cheep-cheep;” KU 330606) from the crater of Mt. Cagua, Location 1a. Photo: RMB.

Platymantis sp. 3 “See-yok”

This suspected new species (Figs 27, 28) was first observed in Old Balbalan Town (Kalinga Province; RMB and ACD, personal observations) and has since been recorded at many sites throughout central and northern Luzon. Morphologically most similar to Platymantis cagayanensis, this species can reliably be identified by its silvery iris (versus the bright yellow-orange iris in Platymantis cagayanensis) and by distinctive advertisement call, sounding to the human ear like “seee-yok…seee-yok” (Brown et al. unpublished data).

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330618–27, PNM 8678–90.

Isabela Province—Location 36: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Platymantis sp. 3 (“See-yok;” specimen not collected) from Location 36. Photo: MVW.

Platymantis sp. 3 (“See-yok;” specimen not collected) from Location 36. Photo: MVW.

Another color variant of Platymantis sp. 3 (“See-yok;” KU 330627) from mid-evelation, Mt. Cagua (Location 1b). Photo: RMB.

Another color variant of Platymantis sp. 3 (“See-yok;” KU 330627) from mid-evelation, Mt. Cagua (Location 1b). Photo: RMB.

Platymantis sp.

Without genetic data, information on mating calls, and/or photographs in life, numerous museum specimens of ground-dwelling, medium sized, dorsally tuberculate members of the genus Platymantis cannot confidently be identified to species. Many have previously been identified by field collectors as Platymantis dorsalis on the basis of generalized morphological similarity to that southern Luzon (type locality: Laguna Bay) species (Brown et al. 1997c; Alcala and Brown 1998, 1999). They are clearly morphologically distinguishable from the terrestrial species Platymantis corrugatus (color pattern differences and presence of dorsolateral dermal tubercular ridges in Platymantis corrugatus), Platymantis sp. 2 “cheep-cheep” (color pattern differences, and absence of any dorsal tubercles in Platymantis sp. 2 “cheep-cheep), Platymantis pygmaeus (much larger body size), and the arboreal species Platymantis cornutus, Platymantis polillensis, and Platymantis sierramadrensis (all of which have expanded finger and toe pads). With on-going taxonomic work, these specimens may be identifiable to Platymantis cagayanensis, Platymantis sp. 1 “Yokyok, ” Platymantis sp. 3 “See-yok” or they may eventually prove to be new, undescribed species.

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330653–713; Location 1b: KU 330714–16; Location 6: USNM 498524–28; Location 13: USNM 498692–93; Location 15: USNM 498731–34.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307611–17.

Family Dicroglossidae

Fejervarya moodiei (Taylor 1920)

Fejervarya moodiei (Fig. 29) is a widespread, endemic estuarine specialist that can be found in a variety of coastal areas including brackish water swamps. Previously considered conspecific with the widespread Southeast Asian species Fejervarya cancrivora, recent genetic evidence suggests that the Philippine populations are genetically distinct; the available name for the Philippine population is Fejervarya moodiei (Kurniawan et al. 2010, 2011). Widespread and common at most coastal areas throughout the Philippines, this species is clearly most appropriately considered “Least Concern” (LC; IUCN 2011).

Cagayan Province—Location 5: PNM 7424; Location 11: PNM 5654, Location 12: PNM 5654, 5675.

Fejervarya moodiei (ACD specimen deposited in PNM) from Ilocos Norte Province. Photo: ACD.

Fejervarya moodiei (ACD specimen deposited in PNM) from Ilocos Norte Province. Photo: ACD.

Fejervarya vittigera (Wiegmann, 1834)

Fejervarya vittigera is a widespread, low elevation species typically observed in highly disturbed areas with standing water (rice fields, ponds and lakes) or along small, denuded streams near coastal areas or canals bordering agricultural areas. Our specimens were found along muddy stream banks in disturbed forests at the edge of agricultural plantations. Although until now this species has always been considered “Least Concern” (IUCN 2011), and not threatened, recent evidence suggests that populations of this endemic low elevation taxon may be in decline (ACD and M. L. Diesmos, personal observation) due to the spread of exceptionally high density populations of the introduced (Diesmos et al. 2006) Asian Bullfrog, Hoplobatrachus rugulosus (see below), which appears to displace, out-compete, or otherwise competitively exclude Fejervarya vittigera in some areas (Brown et al. 2012).

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330225; Location 5: USNM 498529–45, 498973–80; PNM 6256–60; Location 6: USNM 498546; Location 11: USNM 498649; Location 14: USNM 498761–62; Location 19: PNM 6191–93.

Isabela Province—Location 21: 307469.

Hoplobatrachus rugulosus (Wiegmann, 1834)

This introduced species (Fig. 30) was first detected in Laguna province in 1996 (Diesmos et al. 2006), but has since been encountered throughout low-lying valley systems bisecting most major islands in the Philippines. Hoplobatrachus rugulosus achieves remarkable population densities in large areas of rice cultivation and we have witnessed thousands of individuals in a single day’s hike, actively foraging during day light hours, voraciously hunting any potential prey item (including juveniles of their same species and sympatric congeners; ACD and RMB, personal observations). In 2001 RMB and ACD drove the length of the Cagayan Valley, stopping frequently to interview farmers about the densities of frogs in their fields. All reported that these distinctively larger frogs were now the dominant species in the area (and the smaller, previously more common species [presumably Fejervarya vittigera] was now far less common). Additionally, in recent trips to Ilocos Norte (Brown et al. 2012), ACD and party found exceptionally high densities of Hoplobatrachus rugulosus in agricultural areas and along riverbanks and very few native Fejervarya vittigera in the presence of this invasive species.

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330225; Location 3: PNM 9448.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307488.

Hoplobatrachus rugulosus from Minanga (ACD 3159, deposited in PNM). Photo ACD.

Hoplobatrachus rugulosus from Minanga (ACD 3159, deposited in PNM). Photo ACD.

Limnonectes macrocephalus (Inger 1954)

The Luzon fanged frog Limnonectes macrocephalus (Fig. 31) inhabits rivers and streams from sea level up to high elevation forests. Although targeted by humans for food and potentially at risk from predation and competition from invasive species (Diesmos et al. 2006), the Luzon fanged frog has always been characterized as common in mid- to high-elevation forests (Brown et al. 1996, 2000a, 2012; Diesmos et al. 2005; Siler et al. 2011a; McLeod et al. 2011). Although this is Luzon’s largest species, low elevation populations, subject to predation by humans and introduced frog species, consistently have a smaller average body size than do high-elevation populations inhabiting inaccessible montane areas (RMB and ACD, personal observations). The largest individuals have been documented from small, high-elevation mountain streams that lack above ground connections to large rivers at lower elevations (Brown et al. 2000a; Diesmos et al. 2005). Thus, we assume a lack of connectedness has impeded subsistence harvesting in these areas and Limnonectes macrocephalus’ indeterminate growth pattern had allowed these populations to achieve high average body sizes (of up to 350–400 g in males) in the absence of human predation.

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330425–54; Location 1b: KU 330455–69; Location 13: USNM 498704–10, PNM 5888–93; Location 15: USNM 498750–57, 498967–70.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307493–94, 307498–99, 307501–503; Location 22: KU 307506–18; Location 23: KU 327509–17; Location 30: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 36: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Limnonectes macrocephalus (specimens not collected from Dipagsanghan, Location 36. Photo: MVW.

Limnonectes macrocephalus (specimens not collected from Dipagsanghan, Location 36. Photo: MVW.

Limnonectes woodworthi (Taylor 1923)

Limnonectes woodworthi (Fig. 32) is a commonly encountered stream frog in the mountains of southern Luzon and throughout the Bicol Peninsula (Diesmos 1998; Alcala and Brown 1998; Brown et al. 1996, 2000a); more recent studies have determined that this species may also occur farther north, along the foothills of the Sierra Madre Mountains in Aurora Province (Siler et al. 2011a), Isabela Province (ACD, unpublished data), and as far north as Cagayan Province, the Babuyan Islands, and Ilocos Norte Province (Oliveros et al. 2011; Brown et al. 2012). However, the northern populations have a somewhat distinctive color pattern, suggesting they may be taxonomically differentiated. Future studies involving morphometrics, advertisement calls, and genetic data will be necessary to test for the presence of possible species boundaries within Limnonectes woodworthi.

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330227; Location 1b: KU 330226; Location 4: PNM 7523; Location 12: PNM 7522.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307491–92, 307496–97, 307500; Location 23: KU 326471–75.

Limnonectes woodworthi (KU 330226) from mid-elevation Mt. Cagua (Location 1b). Photo: RMB.

Limnonectes woodworthi (KU 330226) from mid-elevation Mt. Cagua (Location 1b). Photo: RMB.

Occidozyga laevis (Günther, 1859)

Occidozyga laevis (Fig. 33) is a common, widespread species known throughout many of the islands and neighboring continental landmasses of Southeast Asia (Inger 1954, 1999; Inger and Voris 2001). Although we have noted body size and call variation at a few sites in the Philippines (ACD and RMB, unpublished data), no taxonomic studies have as of yet targeted this variable taxon. Our specimens were collected along banks of rivers and streams (in quiet side-pools and adjacent puddles), or in puddles on basins on the forest floor, adjacent to flowing water. In the Philippines, individuals aggregate to form breeding groups, with males emitting clicking pulses, sounding to the human ear like the tapping together of small stones.

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330327–52; Location 1b: KU 330353–61, 330717, PNM 5256–63; Location 2: KU 320164–71, 323421; Location 5: USNM 498519; Location 6: USNM 498520–23; Location 15: USNM 498727–19, 499017.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307540–57; Location 23: KU 326478–79; Location 30: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 36: PNM 5179–86; MVW photo voucher.

Occidozyga laevis (specimens not collected) from Dyadyadin (Location 32). Photo: MVW.

Occidozyga laevis (specimens not collected) from Dyadyadin (Location 32). Photo: MVW.

Family Microhylidae

Kaloula kalingensis Taylor 1922

Kaloula kalingensis (Fig. 34) originally was described from Balbalan, Kalinga Province (Taylor 1922a). However, as currently understood, this taxon is now considered common and widespread throughout much of northern Luzon (Brown et al. 1996, 2000a, 2012; Diesmos et al. 2005; Siler et al. 2011a; McLeod et al. 2011; Blackburn et al. in review). Typically encountered in water-filled holes in trees (30–100 cm trunk diameter; holes 1–4 m above the ground) in low to mid-elevation forested areas, this species tolerates high levels of disturbance and is often even found in thick invasive stands of introduced species of bamboo, provided that water-filled cavities provide its favored calling, courtship, breeding, and egg deposition microhabitat (Brown and Alcala 1982; personal observation). These observations recently prompted Brown et al. (2012) to downgrade this species IUCN conservation status from “Vulnerable” (IUCN 2011) to “Near Threatened” (IUCN 2010) and our data support this action. However, recent molecular studies by Blackburn et al. (in review) suggest that Kaloula kalingensis may be a complex of three or four taxonomically distinct entities, which may result in one or more of these putative species (or, at least significant evolutionary units [ESUs] for conservation) to exhibit a more restricted geographical range. If so, the conservation status of these individual putative species (or ESUs) will need to be individually assessed for conservation threats using field-based data of the actual population abundances and distribution (i.e., not inferences from forest cover).

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: 330264–72; Location 1b: KU 330273–78, PNM 7485–89; Location 11: PNM 7461–63.

Isabela Province—Location 34: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Kaloula kalingensis (KU 330273) from forests below the crater of Mt. Cagua (near Location 1a). Photo: RMB.

Kaloula kalingensis (KU 330273) from forests below the crater of Mt. Cagua (near Location 1a). Photo: RMB.

Kaloula picta (Duméril and Bibron, 1841)

Kaloula picta (Fig. 35) is a widespread Philippine endemic, distributed widely in low elevation agricultural areas, along riparian habitats in the foothills of mountain systems, and along low-elevation river valleys and coastal areas (Inger 1954; Brown and Alcala 1970a; Alcala and Brown 1998). Nearly genetically identical throughout the archipelago (Blackburn et al. in review), Kaloula picta may be another species that has recently undergone rapid range expansion as a result of population transplantation in agricultural shipments, coupled with the conversion of most low-elevation coastal floodplains into its preferred habitat (i.e., flooded rice fields; Brown et al. 2010a).

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 17; Location 5: USNM 498516–17; Location 6: 498518; Location 11: USNM 498638–48, PNM 6701–07; Location 12: PNM 6708–12; Location 14: USNM 498719; Location 15: USNM 498720.

Kaloula pulchra is an invasive species (Diesmos et al. 2006) only detected in the country in the last decade and suspected of being introduced through the pet trade. This species has become widely distributed on Luzon and several other islands. Recent observations suggest that, in disturbed habitats, Kaloula pulchra’s impact on native species may be increasing (Brown et al. 2012). We encountered this species in agricultural areas and heavily disturbed riparian habitats (polluted streams near residential areas) along the Cagayan Valley and wide floodplains surrounding the Cagayan River. It is considered “Least Concern” (LC; IUCN 2011).

Cagayan Province—Location 31: no specimens (ACD field observation).

Isabela Province—Cagayan River banks: no specimens (ACD and RMB field observations).

Kaloula picta (KU 330616) from the forest edge just above Barangay Magrafil (near Location 1b). Photo: RMB.

Kaloula rigida (Fig. 36) was described from Baguio City, Benguet Province (Taylor 1922a) and is now known to be widespread in Kalinga, Apayao, Ifugao, and Benguet Provinces of the Cordillera Mountain Range and Isabela and Cagayan Provinces of the northern Sierra Madre (Taylor 1922a; Inger 1954; Alcala and Brown 1998; Diesmos et al. 2005; Brown et al. 2012). This species is a fossorial, ephemeral, pool-breeding specialist that emerges immediately following heavy rains at the onset of the rainy season (June–August) but may be otherwise undetectable if field surveys are conducted in dry months (Brown et al. 2012). Our new records, constituting a major range extension and confirmation of this species continued existence in heavily disturbed forest, further support Brown et al.’s (2012) downgrading of the IUCN (2011) conservation status for this species from “Vulnerable” to “Near Threatened” (IUCN 2010). This species calls in large choruses in temporary pools following heavy rains. Individuals call with repeated pulses, sounding to the human ear like the striking together of two pieces of wood; in large choruses, the collective sound of many individuals calling sounds like a single-stroke engine or small generator.

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330470–74; Location 1b: KU 330475–515; Location 3: PNM 7492; Location 13: PNM 9666–67; Location 15: USNM 498721–16, 498950, 498963–64, 499016.

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 326467–70.

Family Ranidae

Hylarana similis (Günther, 1873)

Hylarana similis (Fig. 37) is ubiquitous throughout Luzon and associated land-bridge islands (Brown and Diesmos 2002, 2009) where it is locally abundant in all riparian habitats sampled (Brown and Guttman 2002). This species ranges from coastal plains near sea level, to the foothills of all of Luzon’s major mountain ranges, where it is particularly abundant, to mid- and high-elevation forested regions. Without any evidence of population declines and considering its wide distribution, Brown et al. (2012) argued for the downgrading of this species from “Vulnerable (IUCN 2010) to “Near Threatened” (IUCN 2010). This latter designation was considered a compromise because although no declines have been noted (and given current IUCN criteria for assessing conservation threat, this species is most appropriately classified as “Least Concern”), recent studies have determined that this species exhibits high levels of chytrid fungus infection at one low elevation site in southwest Luzon (Swei et al. 2011).

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330516–63; Location 1b: KU 330564–84; Location 2: KU 320252–65; Location 12: PNM 8378; Location 13: USNM 498711–15, PNM 8301–05; Location 15: USNM 498758–60, 498972.

Isabela Province—Location 23: 326367–69; Location 30: PNM8371; MVW photo voucher; Location 34: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 36: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Sanguirana luzonensis (Boulenger, 1896)

This widespread, Luzon faunal-region (Brown and Diesmos 2002, 2009) endemic (Fig. 38) is morphologically variable and exhibits a particularly broad set of habitat tolerances, from coastal waterways, to disturbed lowland riparian habitats, and rivers and streams at the foothills of all Luzon mountain ranges. This species is particularly abundant from low- (200–300 m) to high (up to 1700–1800 m) elevation forested areas and appears quite tolerant of anthropogenic disturbances. It is found on rocks, exposed gravel beds, muddy banks, and low, shrub layer vegetation along nearly all of Luzon’s waterways. The major range extensions and wide variety of habitat types reported here support Brown et al.’s (2012) downgrading of the conservation status (IUCN 2011) of this ubiquitous, disturbance-tolerant species, from “Near Threatened” to “Least Concern” (IUCN 2010). Sanguirana luzonensis calls in quiet side pools or when water levels are low and ambient noise is reduced; thus it appears to breed in the late dry season (March–May) and calls with a soft series of descending-frequency “peeps” and “whistles” (Brown et al. 2000a, 2000b; Fuiten et al. 2011).

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330393-95; Location 1b: KU 330396–424; Location 13: USNM 498694–703, PNM 8128–37; Location 15: USNM 498737–49, 498951–52, 498965–66, 499020–21; Location 16: USNM 498735.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307636; Location 23: KU 326491; Location 30: PNM 8162–66, MVW photo voucher; Location 36: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Sanguirana luzonensis female (KU 330408) from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Sanguirana luzonensis female (KU 330408) from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Sanguirana tipanan (Brown, McGuire, and Diesmos, 2000)

The presence of this species (Fig. 39), originally described from Aurora Province (Brown et al. 2000a, b), in Palanan has been confirmed by ACD; to date no specimens are available in museum collections from Cagayan or Isabela Provinces. Although no follow-up surveys have been performed in Palanan, additional surveys in Aurora Province (Siler et al. 2011) have documented this taxon at four new sites, suggesting that it probably no longer qualifies for “Vulnerable” (VU; IUCN 2010, 2011) status. This species was not documented in our extensive montane surveys at the northern tip of Luzon (Mt. Cagua, Municipality of Gonzaga). However, until more fieldwork is conducted in the intervening forested mountains of Isabela and Cagayan Provinces to determine the extent of this species range, little can be interpreted from the apparent northern extent of Sanguirana tipanan’s occurrence at Palanan.

Isabela Province—Location 30: no specimens (ACD photo voucher).

Sanguirana tipanan (CMNH 5582) photographed in Aurora Province (Brown et al. 2000a, b). This species has been ovserved at Location 30 by ACD. Photo: J. McGuire.

Sanguirana tipanan (CMNH 5582) photographed in Aurora Province (Brown et al. 2000a, b). This species has been ovserved at Location 30 by ACD. Photo: J. McGuire.

Family Rhacophoridae

Philautus surdus (Peters, 1863)

A single specimen of this widespread Luzon-region rhacophorid frog has been collected in Palanan. The loud “crunch…crunch” vocalizations of this species have been heard by the authors at Barangay Nassiping, Municipality of Gattaran.

Cagayan Province—Location 3: no specimens (RMB and ACD field observations).

Isabela Province—Location 30: PNM 5378.

Polypedates leucomystax (Gravenhorst, 1829)

Philippine Polypedates leucomystax (Fig. 40) is a genetically distinct variant of a widespread species complex ranging throughout much of Southeast Asia (Inger 1954, 1999; Brown et al. 2010a; Kuriashi et al. 2012). Within the archipelago, this species is genetically identical throughout most of its range, but with two genetic types occurring in the Mindanao faunal region (Brown and Diesmos 2002, 2009), one of which is shared with northern Borneo and southern Peninsular Malaysia, suggesting two invasions of the Philippines (Brown et al. 2010a). The existence of a widespread single haplotype throughout the Philippines suggested to Brown et al. (2010a) that this distribution may have arisen from demographic range expansion following the last several centuries of habitat conversion and human mediated dispersal throughout the country. This species is known from dry, coastal areas near agriculture, to 1000+ m high in the Northern Cordillera where it has been found in pristine forests at high elevation (Diesmos et al. 2005, 2006). Polypedates leucomystax constructs foam nests above water (Brown and Alcala 1982) and calls with loud, single “Craaaak!” or “Plehht!” vocalizations.

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330233; Location 1b: KU 330230–32; Location 3: KU 307624–30; Location 5: USNM 498547–49, 498981–89, PNM 3886–90; Location 6: USNM 498550; Location 7: USNM 498551–53; Location 8: USNM 498554–58; Location 11: USNM 498650–66, PNM 3891–3907; Location 14: USNM 498763; Location 15: USNM 498765–76, 498992–94; Location 17: USNM 498764.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307631–35; Location 22: 307618–23; Location 33: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 36: PNM 3916.

Female Polypedates leucomystax (KU 330233) from the crater of Mt. Cagua, Location 1a. Photo: JS.

Female Polypedates leucomystax (KU 330233) from the crater of Mt. Cagua, Location 1a. Photo: JS.

Rhacophorus pardalis Günther, 1859

This species of Southeast Asian “flying frog” (Fig. 41) is also known from the islands of Indonesia and Malaysia (Brown and Alcala 1994; Alcala and Brown 1998; Inger 1999). In the Philippines it breeds in vegetation above stagnant water in side pools along rivers, water buffalo wallows, or temporary pools in forests. Rhacophorus pardalis constructs foam nests above water (Brown and Alcala 1982) and calls with soft “rattle” or “buzz” (personal observations).

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330279–92; Location 1b: KU 330293–99; Location 15: USNM 498777–82, 499023, PNM 5473.

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 326492–94; Location 32: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 37: PNM 8607.

Rhacophorus pardalis female (KU 330294) from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Rhacophorus pardalis female (KU 330294) from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Rhacophorus appendiculatus (Günther, 1858)

Rhacophorus appendiculatus, although considered widely distributed (Inger 1954, 1999; Brown and Alcala 1994; Alcal and Brown 1998) on numerous Philippine islands, is patchily distributed on Luzon (Brown and Alcala 1994; Siler et al. 2011; McLeod et al. 2011). We have most often encountered this species following heavy rains, in dense choruses surrounding large temporary swamps or pools in forests of varying degrees of disturbance, and at low- to mid-elevations (300–700 m; see Siler et al. 2011a; McLeod et al. 2011). Two recently collected small specimens (Fig. 42) from high-elevation forests on Mt. Cagua appear to fit this species diagnosis (Brown and Alcala 1994) with the caveat that their small body size and reduced tarsal dermal fringes suggest to us at least the possibility that some morphological variation in this group, and possible taxonomic significance if bolstered by future studies of ecology, morphology, habitat, genetic, and call variation.

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330228–29.

Rhacophorus appendiculatus (KU 330228) from the forest in the crater of Mt. Cagua, near Location 1a. Photo: JS.

Rhacophorus appendiculatus (KU 330228) from the forest in the crater of Mt. Cagua, near Location 1a. Photo: JS.

Family Agamidae

Bronchocela marmorata Gray, 1845

We collected individuals of this widespread northern Luzon species (Fig. 43) 4–8 m above the ground in secondary growth trees and agricultural hedgerows. Our specimens are clearly diagnosable, in accordance with Taylor’s (1922b) definition, as Bronchocela marmorata. However at numerous sites throughout the southern portions of Luzon (Brown et al. 2000a, 2012; Siler et al. 2011a; McLeod et al. 2011), specimens appear to match the definition of Bronchocela cristatella (Kuhl 1820; Hallermann 2005), and yet are genetically identical to specimens that key out to Bronchocela marmorata (Hallermann 2005; Brown, Welton, Rock, Siler, and Diesmos, unpublished data). These observations suggest the strong possibility that the characters utilized to define these two nominal species’ on Luzon vary clinally and/or ontogenetically. Clearly, further study is warranted; we note that if, as we suspect, only a single species in this group exists on Luzon (as unpublished genetic data would suggest), the correct name for that species would be Bronchocela marmorata (Taylor 1922b).

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330104–06; Location 2: KU 320283–84; Location 3: PMM 7559; Location 13: USNM 498716; Location 15: USNM 498783; Location 20: PNM 7470.

Male Bronchocela marmorata (KU 330106) from low-elevation, Mt. Cagua (just above Barangay Magrafil), below Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Male Bronchocela marmorata (KU 330106) from low-elevation, Mt. Cagua (just above Barangay Magrafil), below Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Draco spilopterus (Wiegmann, 1834)

This widely distributed Luzon and Visayan faunal-region (Brown and Diesmos 2002, 2009) endemic achieves particularly high densities in coastal coconut palm plantations, but it is also found at lower densities in disturbed and primary forests throughout the northern Philippines (McGuire and Alcala 2000). Our specimens (Fig. 44) were collected in patchy, disturbed (selectively logged) forests at low elevations, adjacent to clearings caused by shifting, slash-and-burn agriculture.

Cagayan Province—Location 2b: KU 330061–62; Location 3: KU 307457–48, 327734, 327736.

Isabela Province—Location 22: KU 327735; Location 25: KU 327737; Location 26: KU 327739; Location 32: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 36: PNM 1007–08; Location 36: PNM 1011–12.

Male Draco spilopterus (KU 330062) from low-elevation, Mt. Cagua (just above Barangay Magrafil), below Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Male Draco spilopterus (KU 330062) from low-elevation, Mt. Cagua (just above Barangay Magrafil), below Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Family Gekkonidae

Cyrtodactylus philippinicus (Steindacher, 1867)